Those of us in the conservative movement find ourselves in a heated and an unfortunate (many times) acrimonious political campaign. Many may think that such is a decline in our political process, but such could not be further from the truth.

I imagine many individuals look upon our founding fathers, though flawed individuals as we all are, as paragons of political wisdom (which they were) and united in the quest for liberty and the establishment of our republic. If that is your perception, allow me to share just a few quotes to forever dispel that thought from your mind. There were numerous rivalries and harsh feelings among many of our foremost founders.

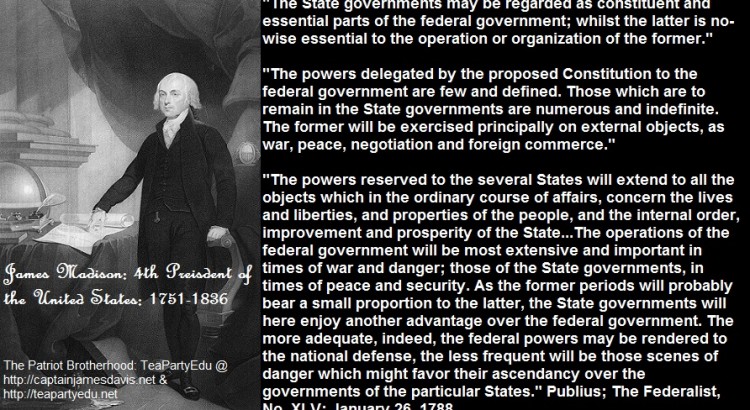

It is no secret of the animosity that existed between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, yet here are the thoughts of James Madison on some of the other founders that may shock you:

“Hancock is weak ambitious a courtier of popularity given to low intrigue and lately reunited by a factious friendship with S. Adams–J. Adams has made himself obnoxious to many particularly in the Southern states by the political principles avowed in this book. Others recollecting his cabal during the war against General Washington knowing his extravagant self importance and considering his preference of an unprofitable dignity to some place of emolument better adapted to private fortune as prof of his having an eye to the presidency conclude that he would not be a very cordial second to the general and that an impatient ambition might even intrigue for a premature advancement. The danger would be the greater if particular factious characters as may be the case, should get into the public councils.” (James Madison, letter to Thomas Jefferson, October 17, 1788)

As for the enmity between Jefferson and Hamilton, consider these words Jefferson penned in a letter to President Washington on September 9, 1792:

“To this justification of opinions, expressed in the way of conversation, against the views of Colo Hamilton, I beg leave to add some notice of his late charges against me in Fenno’s gazette; for neither the stile, matter, nor venom of the pieces alluded to can leave a doubt of their author. Spelling my name & character at full length to the public, while he conceals his own under the signature of “an American” he charges me 1. With…”

They also had the same complaints with the press that many decry today. For example, in a letter to George Washington on October 18, 1787, Madison wrote:

“The Newspapers here begin to teem with vehement & virulent calumniations of the proposed Govt.”

There was also the falling out between the two authors of The Federalist Papers, Madison and Hamilton, that became quite heated as they exchanged essays published from 1793-1794 regarding the role of the presidency and legislature in foreign policy matters.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson became so estranged from one another that they refused to communicate with one another for over twenty years, before being reconciled shortly before their deaths. Their reconciliation was such that when Adams died on July 4, 1826, his last words were “Thomas Jefferson still survives”, not knowing Jefferson had died five hours earlier.

So you see, our current animosity, though unfortunate, is certainly not new. My hope and prayer is that once this primary season is finished, we can be of the same mind as Adams and Jefferson on that semi-centennial day of the signing of our Declaration of Independence.

-March 25, 2016