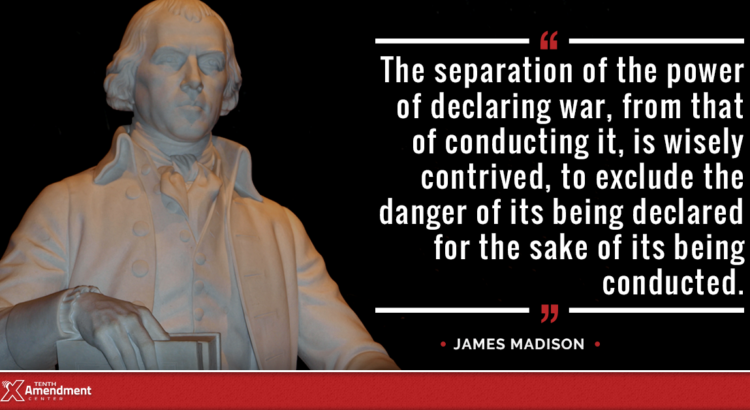

In the previous installment in this series (To Declare or Not to Declare, that Is the Question – Part III), I established the fact that, based upon James Madison’s arguments in an essay dated August 24, 1793 under the pseudonym “Helvidius”, the constitutional authority to “declare war” was reserved to the legislature as this action was tantamount to the passage of a law. Consequently, the president is not authorized to “declare war” on his own any more than he has the authority to enact any other piece of legislation. His role, Madison argued, is strictly that of execution, and unless he is given something to execute (i.e., law), he has no authority.

This being the case, how then does Congress “declare war”? The Constitution is silent on the procedure, but if we proceed from Madison’s supposition that declaring war is a legislative act, then we can safely assume it would follow the course of any other passage of legislation.

As I closed last week’s essay, I pointed out that to declare war requires the action of both houses of Congress, just like the passage of any other law. However, unlike the requirement that all bills relating to raising revenue (i.e., taxes) must originate with the House of Representatives (Article I, Section 7, Clause 1), no mention is given concerning in which chamber such a declaration must originate. This being so, we can assume that it can originate in either chamber. An argument could be made, again extrapolating from Madison’s argument, that since the conclusion of a war via treaty requires action on the part of the Senate, meaning that war cannot be ended without Senate approval, we could say that a bill to commence war would then originate in the Senate, but I believe that might be stretching a little too far. After all, the independence of the States might be at risk in the going to war, but it will be the citizens who will bleed and die, so an equally strong argument could be made that it should originate in the House. However, the safest conclusion is that a bill to declare war can originate in either chamber of Congress.

Once a bill to declare war is passed according to the rules set forth in each chamber, to be official it would then, like any other act of legislation, require the signature of the President. Once signed, then – and only then – would he, as the Commander-in-Chief, have the authority to lead the military forces of the country into war.

But, what if the President said that in his opinion, Congress was full of a bunch of hot-headed war hawks, and that to go to war would be foolish and dangerous and he refused to sign the bill or follow its directives? Could he do this? Would that become an act of treason and be an impeachable offense? The answers are yes he could, and no it would not be an impeachable offense. If the act of declaring war is just like any other piece of legislation, then he can veto it like any other bill, which would then require a 2/3 vote of both the House and the Senate to become law. Once his veto was overridden, then yes, he would be obligated to follow through or be in violation of his oath of office.

Herein we see the wisdom of our founders in their ingenious insertion of checks-and-balances in our system of government. One individual, the President, cannot put the country at risk by declaring war on his own, but neither can a foolish bunch of Senators and Representatives unless the one who will be in command of the battles agrees. More on this next week.

-May 26, 2017