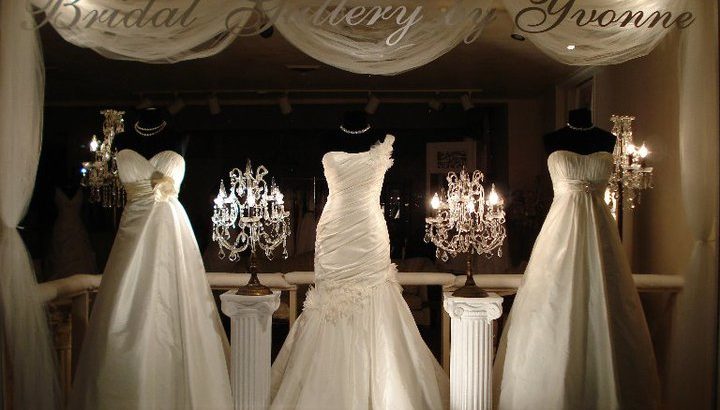

It has just now come to light that a few months ago, in Garland, Texas, 20 armed IRS agents swooped down upon a mom-and-pop bridal store owned by two elderly immigrants from Thailand and seized their entire inventory and equipment for alleged unpaid back income taxes. The designer dresses, valued at around $615,000 were sold for pennies on the dollar along with other assets such as sewing machines, a flat screen television, game console as well as the hat of Vietnam Veteran customer who had left it there to have some patches sewn on. The total net take for the IRS: around $17,000! As a result, this elderly couple is left destitute and out of business after 34 years of operation.

The authority upon which the IRS relied in this robbery is 26 CFR (Code of Federal Regulations) 301.6335-1, “Sale of Seized Property.” Note that this is not a law passed by the national legislature (Congress), but rather is part of the 80,000+ pages of “laws” promulgated by an unelected bureaucracy (IRS) which has both written “laws” (i.e., regulations) – a legislative act, interpreted how to apply these “laws” – a judicial act, and enforced these “laws” – an executive act. Clearly no separation of powers as designed by our founders in the Constitution.

Citizens of the United States are guaranteed the right to protection against such acts by our government: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized” (4th Amendment, US Constitution).

According to news reports, the IRS did obtain court authorization upon their presentation of an affidavit, but the broader question is “Was this ‘reasonable’?” If you read the complete set of guidelines of the CFR I referenced above, it appears the IRS violated its own protocols. Not only this, but in seizing some of the non-clothing items they seized items outside the court’s authorization, especially the hat that belonged to someone not involved in the tax dispute. If you or I do that, it’s called “theft of personal property” and we go to jail!

What is more outrageous is the speed with which this was carried out. According to the CFR there is supposed to be at least a ten-day period between serving notice of the pending sale and the commencement of the sale; but if the IRS believes that the items to be seized are “in jeopardy” of losing their value, the items can be sold immediately without any further due process. Designer bridal dresses “in jeopardy” of losing their value?? Seriously – weddings are going to cease and the dresses be of no worth unless disposed of immediately?

Clearly this action by the IRS costs us taxpayers much more than what they recovered by the sale of these assets. Furthermore, the tax returns for the years in question indicate that the couple had a carryover of a net operating loss, and thus no taxes would have been owed. Also, a memo written by an IRS supervisor obtained via the Freedom of Information Act issued a directive to agents to “shut down this failing business.” If freedom is to be preserved, this insidious income tax and the agency it gave birth to must go.

We are no longer free my fellow Americans. Unelected bureaucrats in these unconstitutional agencies (admittedly the IRS was created to enforce the 13th amendment) tell us what we can do with our property (EPA), what products we can produce (Dept. of Commerce), how much people must be paid by employers (DOL), how we are to obtain health care and related insurances (HHS), and how much disposable money from our earnings we’re allowed to keep (IRS). The government, via these bureaucracies, control our property, our businesses, our health and our incomes, and our representatives in Congress do nothing to stop them. You tell me – if the government controls these critical aspects of our lives (and there’s more), then how is it we can consider ourselves to be “free”?

-July 14, 2017