We’re all familiar with the adage that “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” This adage is one that applies to the third “fix” I wish to address, namely the 14th amendment. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments compose the trio of “reconstruction amendments” that were necessary to ensure that the newly freed slaves in the South were acknowledged to be citizens and entitled to the full rights of white citizens (although there had been a huge number of non-black slaves in the South as well, and these amendments would also have applied to them).

The need for the amendments arose when President Andrew Johnson vetoed as being an unconstitutional overreach of federal power, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that acknowledged these rights as being afforded to the slaves. The former slaves were not being accorded their due rights as citizens and it was determined that it was best to amend the Constitution as that would nullify the president’s veto argument and could not be overturned by a future Congress as easily as a piece of legislation could be. This logic is sound.

However, as well intentioned as this action was, because it was not more clearly defined, the courts over the years have been able to expand upon it and make applications that have led to a major issue with our illegal immigration problem. It was never intended by the authors to grant citizenship to anyone simply because they were born on US soil – that language was inserted to make it clear that the former slaves who had been born on US soil were now to be considered as citizens; futuristic application to those who had not been slaves was never intended. Such is an application of constitutional originalism.

Congress attempted to exercise its power vested in Section 5 of the amendment when Harry Reid of Nevada introduced the Immigration Stabilization Act of 1993 in an effort to correct the misinterpretation of Section 1 of this amendment:

“TITLE X—CITIZENSHIP 4 SEC. 1001. BASIS OF CITIZENSHIP CLARIFIED: “The Congress has determined and hereby declares that any person born after the date of enactment of this title to a mother who is neither a citizen of the United States nor admitted to the United States as a lawful permanent resident, and which person is a national or citizen of another country of which either of his or her natural parents is a national or citizen, or is entitled upon application to become a national or citizen of such country, shall be considered as born subject to the jurisdiction of that foreign country and not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States within the meaning of section 1 of such Article and shall therefore not be a citizen of the United States or of any State solely by reason of physical presence within the United States at the moment of birth.”

A second issue with this amendment is the abuse that has been made over the decades of the so-called “Due Process” clause. It was unfortunate that this was inserted as the Constitution in the 5th amendment already guaranteed this right. Because it was joined in this 14th amendment with the use of the word “person” in conjunction with this clause, it has been interpreted by the courts to mean that all those on US soil are entitled to the rights of citizens in this regard. Again, that is taking this amendment out of its historical context, and as we see has contributed to several of our ills today related to immigration and the attending failure to assimilate into our culture.

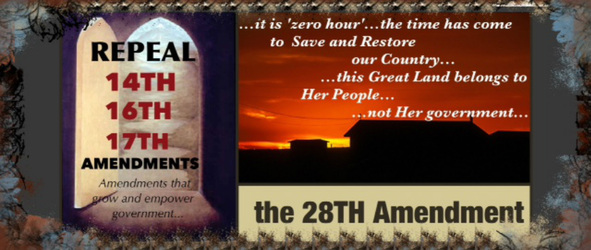

So was this amendment necessary? Yes, unfortunately it was. Yet the amendment clearly illustrates the law of unintended consequences and needs to be rectified, not by statute or court rulings as these can be overturned by future legislation and court rulings, but amended to clarify the meanings that it was originally intended to set in place.

-April 7, 2017